I enjoy grappa all year round. I often drink it after a meal to help me to digest. Sometimes I put a little in my espresso for what the Italians call “caffe corretto.” I like to drizzle grappa on my lemon granita and other fruit ices, and I pour a little in fruit salad. Michele also cooks with grappa, especially in desserts made with chocolate. But when the weather turns cold, as it has done in NYC recently, I just seem to drink more.

Grappa was first called acqua vita, water of life. At one time, it was only a beverage imbibed by farm workers in Northern Italy, especially in the cold months, to give them energy before they went into the fields to work and it was a morning drink taken between the hours of 8:00 AM and 10:00 AM. Southern Italy does not have a tradition of grappa because the weather is too warm. It is only recently, with the popularity and often-high prices that grappa has achieved, that wineries in Southern Italy have utilized their grape pomace (vinaccia in Italian) to make grappa.

Up until about 25 years ago all grappa was what I call traditional, that is, made without being aged in wood. It was clear in color and the flavor reflected the grapes from which it was made.

Traditional grappa Capo di Stato from Loredan Gasparini made from Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet Franc and Malbec.

Today many grappas are aged in new barriques and for the most part they are dark in color. In many cases the wood flavor has taken over.

Making grappa from a wood carving at Marzadro Distilleria in Trentino

Making grappa from a wood carving at Marzadro Distilleria in Trentino

Grappa made from white grapes has more aromas and is easier to drink than grappa made from red grapes, although grappa made from red grapes has more taste. If you are going to introduce grappa to someone for the first time it is better to choose a grappa made from white grapes as it is easier to drink.

Single grape varieties (monovarietal) are produced with pomace from one type of grape. The grape variety can be on the label if at least 85% of the pomace comes from the same grape.

The pomace

Many grappas are produced using pomace from several varieties of grape. If each variety exceeds 15% they must be listed on the label in ascending order.

At a distillery there are 100 days of work, 24/7 from September to December. The freshest selected pomace is distilled each day. The distillation takes place in alembics using the traditional discontinuous bain marie system (steam distillation). The first part of the production called the “head” tastes bad because it contains too much methane (he said it tastes like nail polish) and is therefore discarded. The last part is called the “tail” and contains too many impurities and is also discarded. The discontinuous method produces small amounts of high quality grappa.

The Alembics are handmade out of copper and are excellent conductors of heat. Therefore the particular fragrances and aromas of the pomace (a solid raw material-grape skins) are enhanced to their maximum in order to keep everything uniform. Today almost all distilleries are computerized.

The Alembics are handmade out of copper and are excellent conductors of heat. Therefore the particular fragrances and aromas of the pomace (a solid raw material-grape skins) are enhanced to their maximum in order to keep everything uniform. Today almost all distilleries are computerized.

The continuous process of grappa production in giant stills produces large amounts of grappa. This type of production produces commercial grappa that is not of a very good quality.

After distillation the traditional (clear) grappa is left alone in steel or glass containers. The grappa that is to be aged is placed in barrels of different sizes ranging from 225 liter barriques to 1,500 liter barrels, and even larger. If aged for 12 months, the grappa is called “aged,” and if aged for 18 months, it is called “reserve.” These aged grappas take on different shades of colors from straw yellow to amber. They are smoother than traditional grappa but are much more expensive.

Grappa aging is subject to strict control by Italian customs authorities. Inspectors regularly visit the distillery and put seals on the grappa that has not been bottled to prevent anything being added to the grappa.

I prefer the taste and natural aromas of traditional grappas.

However there are always exceptions, such as the Segni Grappa Riserva aged for 5 years in barrel made from 6 different woods oak, chestnut, ash, cherry, mulberry and juniper from the Mazzetti Distillery in Piedmont.

However there are always exceptions, such as the Segni Grappa Riserva aged for 5 years in barrel made from 6 different woods oak, chestnut, ash, cherry, mulberry and juniper from the Mazzetti Distillery in Piedmont.

Some producers use barrels that were first used to age port and some others age it in terracotta.

Grappa can be infused (steeped) with herbal plants such as ruta (rue), which includes a twig in the bottle, grappa camomilla (chamomile), and fruits, such as grappa di mele (apple), grappa di lamponi (raspberry) to name just a few.

On a “Hello Grappa” press trip, I visited the Bepi Tosolini distillary in FVG and tasted “Grappa Smoked.” Lisa Tosolini, granddaughter of the owner, told us that this grappa is distilled by the traditional method with bain marie pot still. This grappa is made from Friulian red grape skins and then aged in French oak barriques. The oak casks have gone through a toasting process with Kentucky tobacco leaves. This is a dry and intense smoked grappa, which tasted like an aged single malt whiskey. This was a first for me and another new twist to what is being done with grappa.

There are 45 distilleries that produce grappa in Italy. Pomace is the grape residue left after the first pressing when making wine. According to Italian law, an Italian wine producer cannot make grappa, but must send it to a licensed distillery. For example a producer like Banfi will send their pomace to the Bonollo distillery in Siena and tell them what type of grappa they want, traditional (clear), or aged (in barrels) and the alcohol content they want for their grappa.

There are over 4,000 grappa labels on the market today.

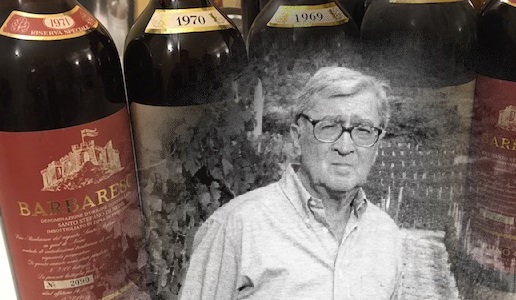

Barolo Riserva 1989 Giacomo Borgogno and Figli 100% Nebbiolo. The grapes come from three different cru vineyards: Cannubi, Liste and Fossati. The winery is located in the center of the town of Barolo. The wine is aged at least five years in large oak barrels. This is a wine produced with traditional and natural wine making methods. Long fermentation and pumping over by hand takes place. Today the Farinetti family that also owns Eataly owns the winery. I have always had very good luck with older vintages of Borgogno. This is a classic traditional Barolo with hints of coffee, licorice, tar, savory meats and a touch of smoke. 1989 was a great vintage for Barolo

Barolo Riserva 1989 Giacomo Borgogno and Figli 100% Nebbiolo. The grapes come from three different cru vineyards: Cannubi, Liste and Fossati. The winery is located in the center of the town of Barolo. The wine is aged at least five years in large oak barrels. This is a wine produced with traditional and natural wine making methods. Long fermentation and pumping over by hand takes place. Today the Farinetti family that also owns Eataly owns the winery. I have always had very good luck with older vintages of Borgogno. This is a classic traditional Barolo with hints of coffee, licorice, tar, savory meats and a touch of smoke. 1989 was a great vintage for Barolo Friuli Style Beef Stew with dried porcini, served with polenta and green beans.

Friuli Style Beef Stew with dried porcini, served with polenta and green beans. Chocolate Chip Biscotti, Ciambellina al Vino Rosso and espresso for dessert

Chocolate Chip Biscotti, Ciambellina al Vino Rosso and espresso for dessert We ended with Vieil Armagnac Jean Cave Distilled in 1983. An elegant aroma of peach syrup, almonds with a touch of pistachio. On the palate structured and complex with notes of licorice and a undertone of smoke.

We ended with Vieil Armagnac Jean Cave Distilled in 1983. An elegant aroma of peach syrup, almonds with a touch of pistachio. On the palate structured and complex with notes of licorice and a undertone of smoke.

Blanc of Cabernet Franc 2019 Halcyon. Made from 100% Cabernet Franc from Contra Costa County on a breezy night in August (according to the label). The grapes arrived at the winery cool to the touch and barely reaching 20 Brix sugar. The clusters were whole pressed and watched to see that the “color” remained clear. This was a surprise wine and it was tasted blind. Because the color was so clear everyone believed it was made from white grapes. The wine is lively with hints of bell pepper, grass, herbs, quince, pears, white flowers and citrus (lime) rind. It is a bit flabby. It is a good summer quaffer. Jason said it would last until 2025 and gave it a 90.

Blanc of Cabernet Franc 2019 Halcyon. Made from 100% Cabernet Franc from Contra Costa County on a breezy night in August (according to the label). The grapes arrived at the winery cool to the touch and barely reaching 20 Brix sugar. The clusters were whole pressed and watched to see that the “color” remained clear. This was a surprise wine and it was tasted blind. Because the color was so clear everyone believed it was made from white grapes. The wine is lively with hints of bell pepper, grass, herbs, quince, pears, white flowers and citrus (lime) rind. It is a bit flabby. It is a good summer quaffer. Jason said it would last until 2025 and gave it a 90. We started with two kinds of crostini, one topped with homemade roasted peppers and mozzarella and the other with mozzarella and anchovies.

We started with two kinds of crostini, one topped with homemade roasted peppers and mozzarella and the other with mozzarella and anchovies. Fiorano Bianco 1995 Boncompagni Ludovisi Principe di Verosa made from 100% Malvasia Candia. I have had this wine a number of times and this was one of the best bottles I have tasted. There is a slight touch of oxidation with aromas of melon, honey wax and Queen Ann cherries. On the palate there are slight mineral notes with lots of flesh, good acidity and a medium long finish. Jason gave it a 92. I gave it 88 but after having it with food I gave it a 90. Jason said it would last until 2030.

Fiorano Bianco 1995 Boncompagni Ludovisi Principe di Verosa made from 100% Malvasia Candia. I have had this wine a number of times and this was one of the best bottles I have tasted. There is a slight touch of oxidation with aromas of melon, honey wax and Queen Ann cherries. On the palate there are slight mineral notes with lots of flesh, good acidity and a medium long finish. Jason gave it a 92. I gave it 88 but after having it with food I gave it a 90. Jason said it would last until 2030. Sauce for pasta cooking

Sauce for pasta cooking Montesecondo IGT Toscana 2019 Silvio Messana made from 100% Sangiovese from two different biodynamical properties in the San Casciano zone of Chianti Classico. The original (Montesecondo) is lower, warmer with heavy clay soil in the town of Cerbaia. Vignano (village) vineyard is at 500 meters and much cooler and rich in limestone. The grapes come from younger vines and are picked early. Harvest is by hand most but not all of the bunches are destemmed. Varying proportions of whole bunches layered with whole berries go into concrete fermentation tanks. Fermentation takes place with natural yeasts and no sulfur is added. Maceration is short and there are no punch downs or other extractive measures. Aging is in concrete tanks for about a year. The wine has aromas of light red cherries, dried cranberries and herbs. This is a medium bodied wine with nice acidity. Jason gave it a 92.

Montesecondo IGT Toscana 2019 Silvio Messana made from 100% Sangiovese from two different biodynamical properties in the San Casciano zone of Chianti Classico. The original (Montesecondo) is lower, warmer with heavy clay soil in the town of Cerbaia. Vignano (village) vineyard is at 500 meters and much cooler and rich in limestone. The grapes come from younger vines and are picked early. Harvest is by hand most but not all of the bunches are destemmed. Varying proportions of whole bunches layered with whole berries go into concrete fermentation tanks. Fermentation takes place with natural yeasts and no sulfur is added. Maceration is short and there are no punch downs or other extractive measures. Aging is in concrete tanks for about a year. The wine has aromas of light red cherries, dried cranberries and herbs. This is a medium bodied wine with nice acidity. Jason gave it a 92. For our first course, we had Bucatini alla Matriciana, one of Rome’s classic pastas and my favorite. It is made with guanciale (cured pork cheek), onion, tomatoes and a little hot pepper.

For our first course, we had Bucatini alla Matriciana, one of Rome’s classic pastas and my favorite. It is made with guanciale (cured pork cheek), onion, tomatoes and a little hot pepper. Our main course was rack of lamb with a Parmigiano-Reggiano crust. Here it is ready for the oven

Our main course was rack of lamb with a Parmigiano-Reggiano crust. Here it is ready for the oven The lamb ready to serve

The lamb ready to serve

Homemade seeded sourdough bread made by Jason De Salvo

Homemade seeded sourdough bread made by Jason De Salvo

We started with a simple version of Croque Monsieur, a grilled prosciutto and cheese sandwich.

We started with a simple version of Croque Monsieur, a grilled prosciutto and cheese sandwich. Hermitage 1999 “La Chapelle” Paul Jaboulet Aine made from 100% Syrah planted in a diversity of terroir. The age of the vines is 40 to 60 years. The grapes come down from the slopes of l’Hermitage on small sledges and then are sorted manually and vinified traditionally in the cellars. The final assembly is made during aging in the cellars in wood for 15 to 18 months. During this time the wines are also racked. This is a complex and elegant wine showing no signs of age. It has hints of black fruit, black cherries, spice and leather. It has a long finish and very pleasing aftertaste and is a very impressive wine. It was the perfect companion to the meal because of the depth of the aromas and flavors.

Hermitage 1999 “La Chapelle” Paul Jaboulet Aine made from 100% Syrah planted in a diversity of terroir. The age of the vines is 40 to 60 years. The grapes come down from the slopes of l’Hermitage on small sledges and then are sorted manually and vinified traditionally in the cellars. The final assembly is made during aging in the cellars in wood for 15 to 18 months. During this time the wines are also racked. This is a complex and elegant wine showing no signs of age. It has hints of black fruit, black cherries, spice and leather. It has a long finish and very pleasing aftertaste and is a very impressive wine. It was the perfect companion to the meal because of the depth of the aromas and flavors. Quail in the pan. Michele braised them with prosciutto, sage and white wine. They were meltingly tender.

Quail in the pan. Michele braised them with prosciutto, sage and white wine. They were meltingly tender. Quail in the dish, with roasted Brussels sprouts and mashed potatoes.

Quail in the dish, with roasted Brussels sprouts and mashed potatoes. Dessert was pears poached in white wine with lemon and cinnamon. Topped with a few raspberries.

Dessert was pears poached in white wine with lemon and cinnamon. Topped with a few raspberries. Café and my favorite red wine and fennel taralli cookies, which always remind me of Rome.

Café and my favorite red wine and fennel taralli cookies, which always remind me of Rome.

For starters, Michele made crostini with toasted ciabatta bread topped with marinated roasted peppers and shavings of Parmigiano-Reggiano.

For starters, Michele made crostini with toasted ciabatta bread topped with marinated roasted peppers and shavings of Parmigiano-Reggiano.

Pasta ready to serve

Pasta ready to serve Mezze Maniche with cherry tomato sauce and fresh bufala ricotta.

Mezze Maniche with cherry tomato sauce and fresh bufala ricotta. Peppers, onions and potatoes ready for the oven. When partially cooked, Michele add sausages to the pan.

Peppers, onions and potatoes ready for the oven. When partially cooked, Michele add sausages to the pan.

Irpinia Aglianico 2016 “Memini” Az. Ag. Guastaferro made from 100% Aglianico. The wine bursts with sweet ripe fruit flavors of cherry, raspberry, strawberry and pomegranate. It has a wonderful fruit filled finish and a very long aftertaste. It was a very interesting Aglianico and I have never tasted one like this before. Daniele Cernilli (aka Doctor Wine) in his book The Essential Guide to Italian Wine 2020 states: … In 2002 Raffaele Guastaferro inherited 10 hectares from his grandfather with over 100 year old vines trained using the old starseto (pergola Avellinese) method…creating a very interesting style for the wines that were also based on tradition. I liked this wine so much when I had it for Christmas at the home of Tom Maresca and Diana Darrow that I wanted to serve it to my guest.

Irpinia Aglianico 2016 “Memini” Az. Ag. Guastaferro made from 100% Aglianico. The wine bursts with sweet ripe fruit flavors of cherry, raspberry, strawberry and pomegranate. It has a wonderful fruit filled finish and a very long aftertaste. It was a very interesting Aglianico and I have never tasted one like this before. Daniele Cernilli (aka Doctor Wine) in his book The Essential Guide to Italian Wine 2020 states: … In 2002 Raffaele Guastaferro inherited 10 hectares from his grandfather with over 100 year old vines trained using the old starseto (pergola Avellinese) method…creating a very interesting style for the wines that were also based on tradition. I liked this wine so much when I had it for Christmas at the home of Tom Maresca and Diana Darrow that I wanted to serve it to my guest. On the plate

On the plate Dessert was simple. Red Wine Cookies and espresso.

Dessert was simple. Red Wine Cookies and espresso.

Making grappa from a wood carving at Marzadro Distilleria in Trentino

Making grappa from a wood carving at Marzadro Distilleria in Trentino

The Alembics are handmade out of copper and are excellent conductors of heat. Therefore the particular fragrances and aromas of the pomace (a solid raw material-grape skins) are enhanced to their maximum in order to keep everything uniform. Today almost all distilleries are computerized.

The Alembics are handmade out of copper and are excellent conductors of heat. Therefore the particular fragrances and aromas of the pomace (a solid raw material-grape skins) are enhanced to their maximum in order to keep everything uniform. Today almost all distilleries are computerized.